March 30, 2019

New collaborative research from the Weizmann Institute of Science has asked a different question about the bacteria in our microbiomes, and the answers, recently published in Nature, could help target disease more precisely.

Our gut microbiome – the complement of bacteria we carry around in our intestines – has been linked to everything from obesity and diabetes, to heart disease and even neurological disorders and cancer.

In recent years, researchers have been sorting through the multiple bacterial species that populate the microbiome, asking which of them can be implicated in specific disorders. But the Weizmann research addressed a new question: “What if the same microbe is different in different people?”

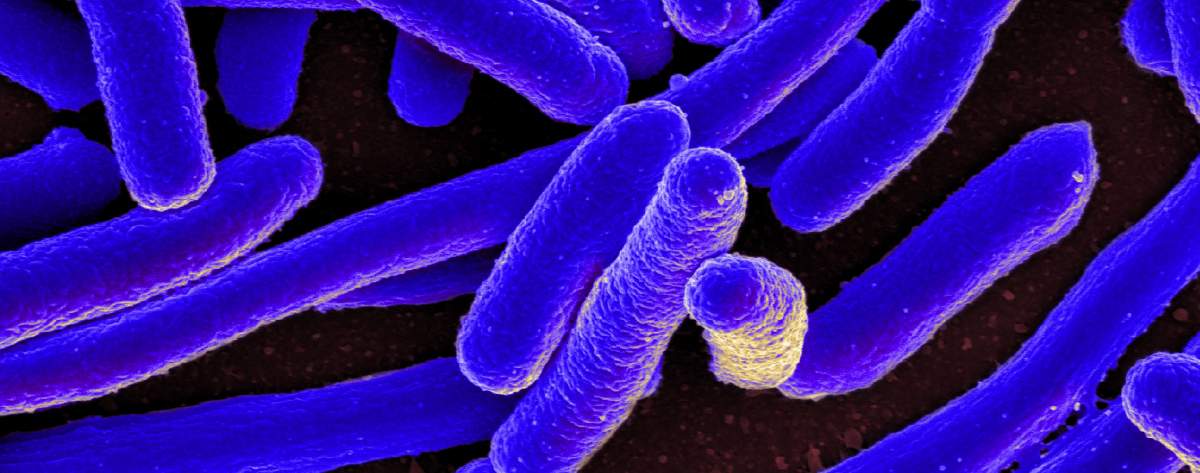

For some time it has been known that microbe genomes are not fixed from birth, as humans are. They are able to lose genes, exchange genes with other microorganisms, or gain new ones from their environment.

Therefore, a detailed comparison of the genomes of seemingly identical bacteria will reveal sequences of DNA that occur in one genome and not others, or possibly sequences that appear just once in one and several times over in others.

These differences are called structural variants. Structural variants – even tiny ones – can translate into huge differences in the ways that microbes interact with their human hosts. A variant might be the difference between a benign presence and a pathogenic one, or it could give bacteria resistance to antibiotics.

Drs David Zeevi and Tal Korem, initially in the lab of Professor Eran Segal in the Weizmann Institute of Science and then in their present positions at Rockefeller and Columbia Universities, developed algorithms that systematically identify structural variants across human gut microbiomes.

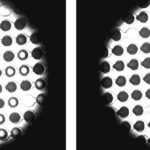

The researchers began with microbiomes from nearly 900 Israeli subjects, in which they succeeded in identifying over 7,000 variants. Next, they formed a collaboration with Dutch researchers from the University of Groningen, in the Netherlands, and looked for these variants in the microbiomes of a large group of Dutch subjects.

The found that most of the structural variants they had identified in the Israeli subjects could also be found among the Dutch ones, despite the differences in genetics and lifestyle between the groups.

The scientists next asked whether any of the structural variants they had identified are associated with health or disease. The group turned up more than 100 that were associated with risk factors for disease. Many of these associations were again replicated in the Dutch cohort.

In one case, individuals who had a certain variant present in the genome of a particular microbial species in their microbiome, were 6kg thinner and had a 4cm narrower waist, on average, than individuals who had the same microbe but did not harbour that particular variant.

The scientists then analysed the genes encoded on this variant and found that it gave the bacterium the potential ability to turn certain sugars into a substance called butyrate. Butyrate is a small fatty acid that smells like rancid butter (thus its name, from the Ancient Greek for ‘butter’). Despite its odour, butyrate has been shown to have anti-inflammatory effects and a positive influence on metabolism. This ability, say the scientists, could help explain the weight difference between those carrying bacteria with and those without the structural variant.

The finding suggests the method the group developed could help researchers pinpoint the connections between our microbiome, health and disease in significant ways that might be missed with other means.

“The real potential of this approach is that it allows us to look for the actual mechanisms behind the associations we find,” said Zeevi.

Segal said he estimated there may be tens of thousands of structural variants within the human gut microbiome and thousands of these could be associated with disease and disease risk.

Since the makeup of the microbiome has been implicated in so many different syndromes and disorders, this research could have a lasting impact on the search for better, more targeted probiotics for treating disease.

Tagged: cancer, fat, heart disease, microbiome, Nature, Netherlands, obesity, probiotics, Segal, University of Gronginen, weight, Weizmann