September 29, 2018

The recovery rates in new immunotherapy treatments for melanoma have risen dramatically, in some cases to around 50%, but these could go higher. A new study led by researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science and recently published in Cancer Discovery, showed that in lab dishes and animal studies a highly personalised approach could help immune cells improve their abilities to recognise the cancer and kill it.

Today’s immunotherapies involve administering antibodies to unlock the natural immune T cells that recognise and kill cancer cells; or else growing and reactivating these T cells outside the body and returning them in a ‘weaponised’ form.

“But none of this will kill the cancer if the immune cells do not recognise the ‘signposts’ that mark cancer cells as foreign,” said Professor Yardena Samuels of the Institute’s Molecular Cell Biology Department.

Groups around the world are searching for such signposts – mutated peptides known as neo-antigens on the cancer cells’ outer membranes. Identifying the particular peptides that present themselves to the T cell can then help develop personalised cancer vaccines based on neo-antigen profiles.

One of the problems in uncovering neo-antigens in cancers like melanoma, however, is that they are presented by a protein complex called HLA – a complex that can come in thousands of versions, even without the addition of cancerous mutations. Indeed, the algorithms that are often used to search the cancer-cell genome for possible neo-antigens had predicted hundreds of possible candidates.

Samuels, together with her PhD student, Shelly Kalaora, and in collaboration with Professor Arie Admon of the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, bypassed the algorithm methods, using a method Admon had developed to remove the peptides from the melanoma cells’ HLA complex and investigate their interactions with T cells.

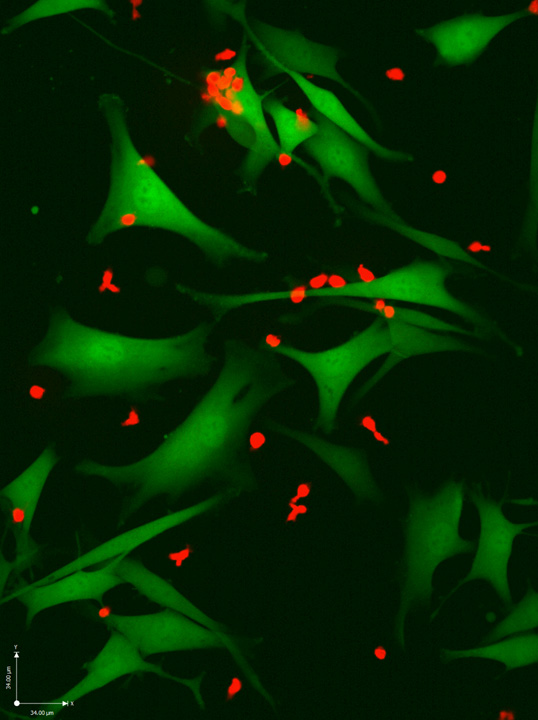

“We discovered that tumors present many fewer neo-antigens than we expected. Our neo-antigen and corresponding T-cell-identification strategies were so robust, our neo-antigen-specific T cells killed 90% of their target melanoma cells both on plates and in mice,” said Samuels.

“This suggests possible clinical applications for the near future. Some of the peptides we identified are neo-antigens that had not even shown up in the algorithm studies; in other words, the method we used, called HLA peptidomics, is really complementary to these methods.”

Samuels and Kalaora worked with a team that included Dr Eytan Ruppin of the National Cancer Institute, USA; Dr Jennifer Wargo of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and Professor Nir Friedman of the Weizmann Institute of Science’s Molecular Cell Biology Department.

For some of the patients in the group had obtained multiple samples, and this enabled them to ask questions about metastasis – for example, whether the same neo-antigens were present on secondary tumors after the cancer had spread to other organs.

“This is the first time that HLA peptide studies of multiple metastases derived from the same patient have ever been performed,” said Kalaora.

“The significant similarity between the various HLA-peptidomes has strong implications for the process of choosing neo-antigens for patient treatment, showing that it is clearly essential not only to identify the immunogenic peptides presented on the cancer cells, but to select the ones that are common to the patient’s metastases. This can then help direct systemic therapeutic responses in patients with multiple metastases.”

A new drug for every patient

The group then took their findings one step further: Using natural T cells extracted from 14 of the patients, the researchers identified those that most strongly react with the neo-antigens. They sequenced the genomes of these cells, grew them and tested them in animal models with the patients’ tumor cells. In both lab dish experiments and mice, they showed that the response of the T cells they identified was highly effective in fighting the cancer.

“Although this research is experimental right now, the findings are highly relevant to clinical research, as groups around the world have already worked out the basics of developing therapeutic anti-cancer treatments based on neo-antigens,” pointed out Samuels.

“As almost all the neo-antigens detected in patients thus far are individual – and unique to the particular cancerous tissue – they constitute an ideal class of anti-cancer targets. This would be the ultimate ‘personalised’ cancer therapy – a new drug is created for every patient.”

Also participating in this research were Yochai Wolf, Dr Itay Tirosh, Nouar Qutob, Polina Greenberg and Ronen Levy of the Molecular Cell Biology Department; Professor Guy Shakhar, Tali Feferman, Erez Greenstein and Dan Reshef of the Immunology Department; and Ofra Golani of the Life Sciences Core Facilities Department, all of the Weizmann Institute of Science; Eilon Barnea of the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology; Alexandre Reuben, Jianhua Zhang, Xizeng Mao, Xingzhi Song, Chantale Bernatchez, Cara Haymaker, Marie-Andrée Forget, Caitlin Creasy, Brett Carter and Zachary Cooper of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center; Sushant Patkar of the National Cancer Institute, USA; Juliane Quinkhardt and Tana Omokoko of BioNTech Cell & Gene Therapies, Germany; Professor Steven Rosenberg of the National Cancer Institute, USA; Michal Lotem of the Hadassah Medical School, Jerusalem, Israel; and Ugur Sahin of University Medical Center of Johannes Gutenberg University, Mainz, Germany.