July 7, 2016

The Weizmann Institute of Science’s Dr Yohai Kaspi is part of the Juno Science team that hopes to answer some burning questions about the largest planet in the Solar System.

As reported this week in The Jerusalem Post, on Monday July 4, NASA’s Juno spacecraft entered orbit around Jupiter, the largest planet in the Solar System. Its extended trip – more than 2 billion kilometers over nearly five years – is now over, but its work is just beginning. Following some intricate maneuvers, the spacecraft went into a unique 14-day orbit that will allow it to get as close as 4000 km above the cloud tops of the planet – much closer than any mission ever before flown.

Dr Yohai Kaspi said this was a unique opportunity for science.

“For the first time we will have an opportunity to study the flows beneath the thick clouds we see covering Jupiter,” he said.

Kaspi, who is part of the Juno Science team, and Institute staff scientist Dr Eli Galanti, were at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, along with the other scientists and engineers on the Juno team, to witness the event.

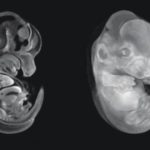

Among the many questions Kaspi, Galanti and their colleagues would like to answer is this: How deep are the weather patterns we observe on Jupiter’s surface? These patterns are gas flows that appear as ordered stripes on the planet’s outer surface, and because there is no solid ground to disrupt them, they may extend very deep into the interior. Adding the third dimension to our understanding of these patterns could help to answer any number of other questions, including how do these patterns form, whether the outer layers rotate in sync with the inner ones, how thick is the famous Great Red Spot, and whether the planet has a solid inner core, which is key for understanding how planets form.

Kaspi, who has been with the Juno project nearly a decade, has used the interval to work out the tools for analyzing measurements that will be taken of the planet’s gravity. Since weather – the movement of mass around the planet – creates slight variations in the planet’s gravity at different points, Kaspi and his team will use the data from Juno’s measurements of the gravitational fields to “reverse calculate” the wind patterns that modified them.

In this way, he will help scientists “peer for the first time beneath the thick cloud layer” of Jupiter. Kaspi has already applied these tools to calculating the depth of weather patterns on Uranus and Neptune, showing that the high winds on these planets are confined to a relatively shallow upper layer, as well as to analyzing measurements of Jupiter and Saturn obtained from Earth-bound telescopes. But the Juno mission will provide the first opportunity to measure the differences in Jupiter’s gravitational fields precisely and accurately, and thus develop a clearer picture of the planet’s interior and atmospheric dynamics.