November 15, 2019

A new study on mice, recently published in Nature Neuroscience, shows animal research may need to take into account the connection between genes, behaviour and personality.

We may refer to someone’s personality as ‘mousey’ but in truth mice have a range of personalities nearly as great as our own.

Professor Alon Chen and members of two groups he heads – one in the Weizmann Institute of Science’s Neurobiology Department and one in the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry in Munich, Germany – decided to explore personality specifically in mice.

This study enabled them to develop a set of objective measurements for this highly slippery concept. A quantitative understanding of the traits that make each animal an individual might help answer some of the open questions in science concerning the connections between genes and behaviour.

Dr Oren Forkosh, then a postdoctoral fellow who led the research in Chen’s group in Germany, explained that for scientists, understanding how genetics contribute to behaviour has remained an open question.

“Personality, we hypothesized, might be the ‘glue’ that binds the two together: Both genes and epigenetics – which determine how the genes are expressed – contribute to personality formation; in turn, one’s personality will determine, to a great extent, how one behaves in any given situation,” he said.

Personality is by definition something that is both individual for each animal and remains fairly stable for an animal over its lifetime.

Human subjects are generally given personality scores based on multiple-choice questionnaires, but for mice, the researchers needed to start with their behaviour and work backward.

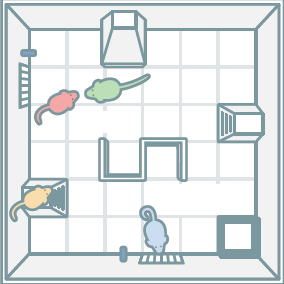

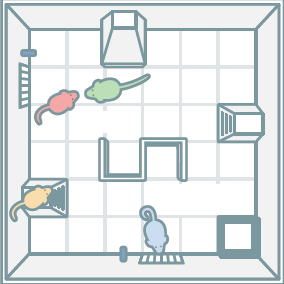

The mice were color-coded for identification, placed in small groups in regular lab environments – with food, shelter, toys, etc. – and allowed to interact and explore freely. They were then videoed over several days and their behaviour analysed in depth. The scientists identified 60 separate behaviours. For example, approaching others, chasing or fleeing, sharing food or keeping others away from food, exploring or hiding.

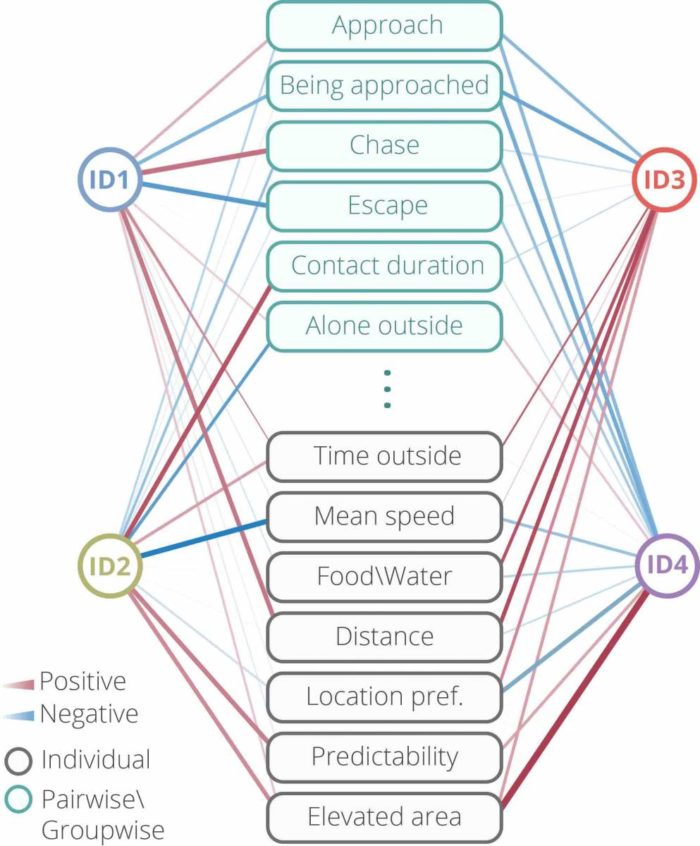

Next the group created a computational algorithm to extract personality traits from the data on the mice’s behaviour. This method works something like the five-part personality score used for humans in which subjects are graded on sliding scales that rate extroversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism and openness to experience.

For mice, the algorithms revealed four such sliding scales, and although the researchers refrained from assigning anthropomorphic labels to these ratings, they can be applied very much like the human ones. That is, each scale is linear, with opposites at either end; when the group assigned the mice personality types based on their scores for these traits, they found that each mouse could be seen to have a unique, individual personality that consistently informed its behaviour.

To see if these traits were stable the researchers mixed up the groups – a stressful situation for the mice. They found that some of the behaviours changed – sometimes drastically – but what they had assessed as personality remained the same.

But what can now be learned from a method for assessing a mouse’s personality?

Working with Professor Uri Alon of the Institute’s Molecular Cell Biology Department, the team used the linear scales they had developed to plot a ‘personality space’ in which two of the traits were compared.

This sort of analysis yields a triangle in which archetypes inhabit the corners (for example, highly dominant and non-commensal (country mice that are not human-friendly), dominant but commensal (city mice), and subordinate). When traits are viewed this way, they can point to evolutionary trade-offs – for example, in the need to survive and thrive in a dominance hierarchy.

“In fact we see that these archetypes – and all the shades in between – are quite natural. These traits have not been bred out of our mice, even though they have lived for generations in labs and could probably not survive in the wild,” said Forkosh.

The researchers also mapped gene expression patterns in the brains of these mice, and they found that they could identify a number that were associated with certain personality traits they had identified.

“This method will open doors to all sorts of research. If we can identify the genetics of personality and how our children inherit certain aspects of their personalities, we might also be able to diagnose and treat problems when these genes go wrong,” said Forkosh.

“In future we might even be able to use these insights to develop more personalized psychiatry, for example, to be able to prescribe the proper treatments for depression. In addition, we can use the method to compare personality across species, and thus to gain insight into the animals that share our world,” he concluded.

Professor Alon Chen is the President-Elect of the Weizmann Institute of Science. Also participating in this research were Stoyo Karamihalev, Sergey Anpilov and Yair Shemesh of the Weizmann Institute of Science and the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry, Markus Nussbaumer, Cornelia Flachskamm and Paul M. Kaplick and Simone Roeh of the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry and Chadi Touma of the University of Osnabrück, Germany.

Four mice in a well-stocked cage exhibited around 60 different behaviors for evaluation

Based on the 60 behaviors, an algorithm found those relevant to personality, and mapped out four scales for assessing mouse personality