September 30, 2022

Cancer tumours contain multiple species of fungi that differ per tumour type, according to a large study led by researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science and the University of California, San Diego.

The study, published today in Cell, potentially has implications for the diagnosis and treatment of cancer, as well as for the detection of cancer through a blood test. It complements scientists’ understanding of the interaction between cancer cells and the bacteria that exist in tumours alongside fungi, bacteria that have been shown to affect cancer growth, metastasis and response to therapy.

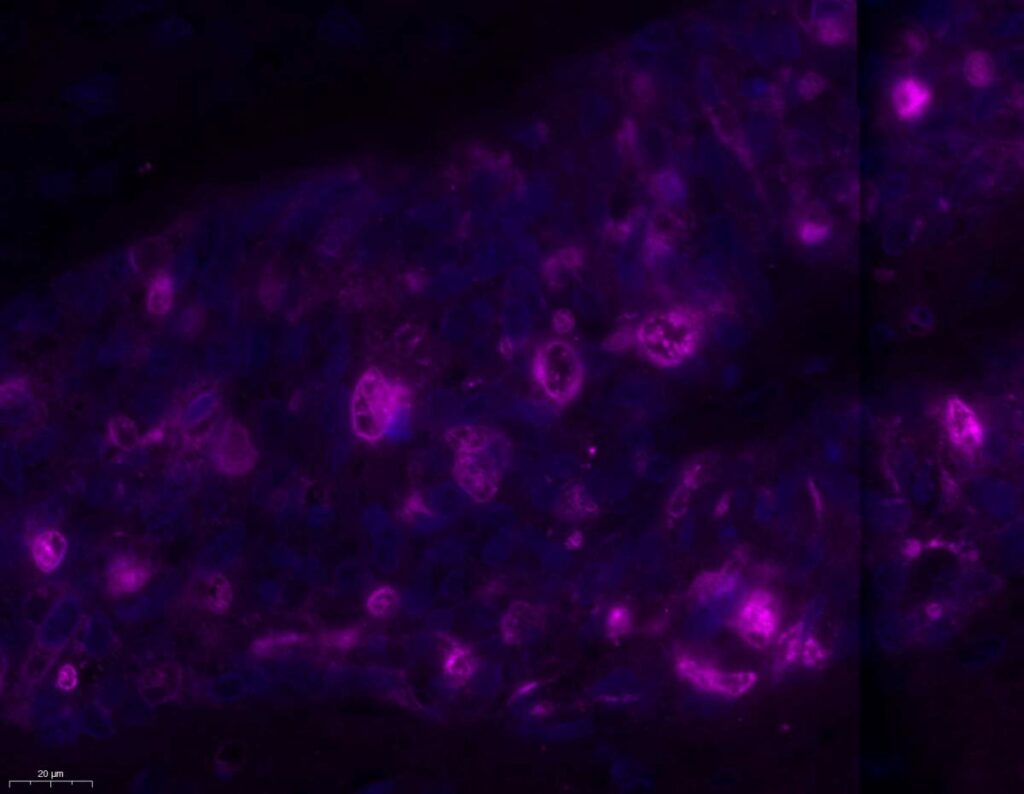

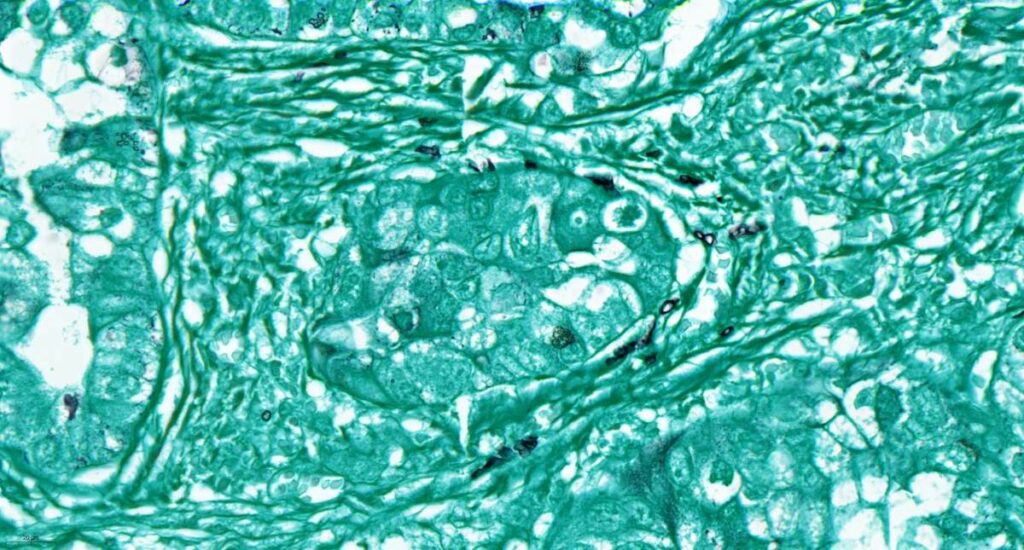

The researchers systematically profiled fungal communities in more than 17,000 tissue and blood samples taken from patients with 35 types of cancer. They found that fungi can be detected in all of these cancer types. Fungi were mostly found ‘hiding’ inside the cancer cells or in immune cells inside the tumours.

The study also revealed multiple correlations between the presence of specific fungi in tumours and conditions related to treatment. For example, breast cancer patients who have Malassezia globosa – a fungus found naturally on the skin – in their tumours had a much lower survival rate than those who did not have the fungus. In addition, specific fungi were found to be more prevalent in the breast tumours of older patients than in those of younger ones, in the lung tumours of smokers than in those of non-smokers and in melanoma tumours that did not respond to immunotherapy than in tumours that did respond to therapy.

According to Professor Ravid Straussman of the Weizmann’s Molecular Cell Biology Department, co-leader of the study, these findings suggest that fungal activity is a new and emerging hallmark of cancer.

“These findings should drive us to better explore the potential effects of tumour fungi and to re-examine almost everything we know about cancer through a microbiome lens,” he said.

The study, which characterized both the fungi and the bacteria that are present in human tumours, demonstrated that typical “hubs” of fungi and bacteria can be found in tumours. For example, while tumours that contain Aspergillus fungi tend to have specific bacteria in them, other tumours that contain Malassezia fungi tend to have other bacteria in them. These different ‘hubs’ may be important for treatment, as they correlated with both tumour immunity and patient survival.

“This study sheds new light on the complex biological environment within tumours, and future research will reveal how fungi affect cancerous growth,” said Professor Yitzhak Pilpel, a co-author of the study and a principal investigator at the Weizmann Institute of Science’s Molecular Genetics Department.

“The fact that fungi can be found not only in cancer cells but also in immune cells implies that, in the future, we’ll probably find that fungi have some effect not only on the cancer cells but also on immune cells and their activity.”

The existence of fungi in most human cancers “is both a surprise and to be expected,” says Rob Knight, a Professor of Paediatrics, Bioengineering and Computer Science and Engineering at UC San Diego, who co-authored the study.

“It is surprising because we don’t know how fungi could get into tumours throughout the body. But it is also expected, because it fits the pattern of healthy microbiomes throughout the body, including the gut, mouth and skin, where bacteria and fungi interact as part of a complex community.”

The new paper also explored the presence of fungal and bacterial DNA in human blood. “The results suggest that measuring microbial DNA in the blood may help in the early detection of cancer, as different microbial DNA signatures can be found in the blood of cancer and noncancer patients,” says Dr Gregory Sepich-Poore, a former graduate student in Knight’s lab.

Last year, Knight and Sepich-Poore cofounded Micronoma, a company developing a platform that uses microbial biomarkers in blood for the early diagnosis of cancer.

At the Weizmann Institute, the study was led by first coauthors Dr Lian Narunsky Haziza from Straussman’s and Pilpel’s labs and by Dr Ilana Livyatan from Straussman’s lab. Other collaborators include Omer Asraf, Dr Deborah Nejman, Dr Nancy Gavert, Ruthie Ariel and Arnon Meltser of the Weizmann Institute of Science; Dr Amir Bashan and Guy Amit of Bar-Ilan University; Professor Iris Barshack, Dr Nora Balint-Lahat and Gili Perry of Sheba Medical Center and Tel Aviv University; Dr Einav Gal-Yam and Dr Maya Dadiani of Sheba Medical Center; Cameron Martino, Dr Antonio González, Dr Justin P. Shaffer, Dr Sandip Pravin Patel and Dr Austin D. Swafford of UC San Diego; Professor Jason E. Stajich of UC Riverside; Dr Qiyun Zhu of Arizona State University; and Dr Stephen Wandro of Micronoma, San Diego.

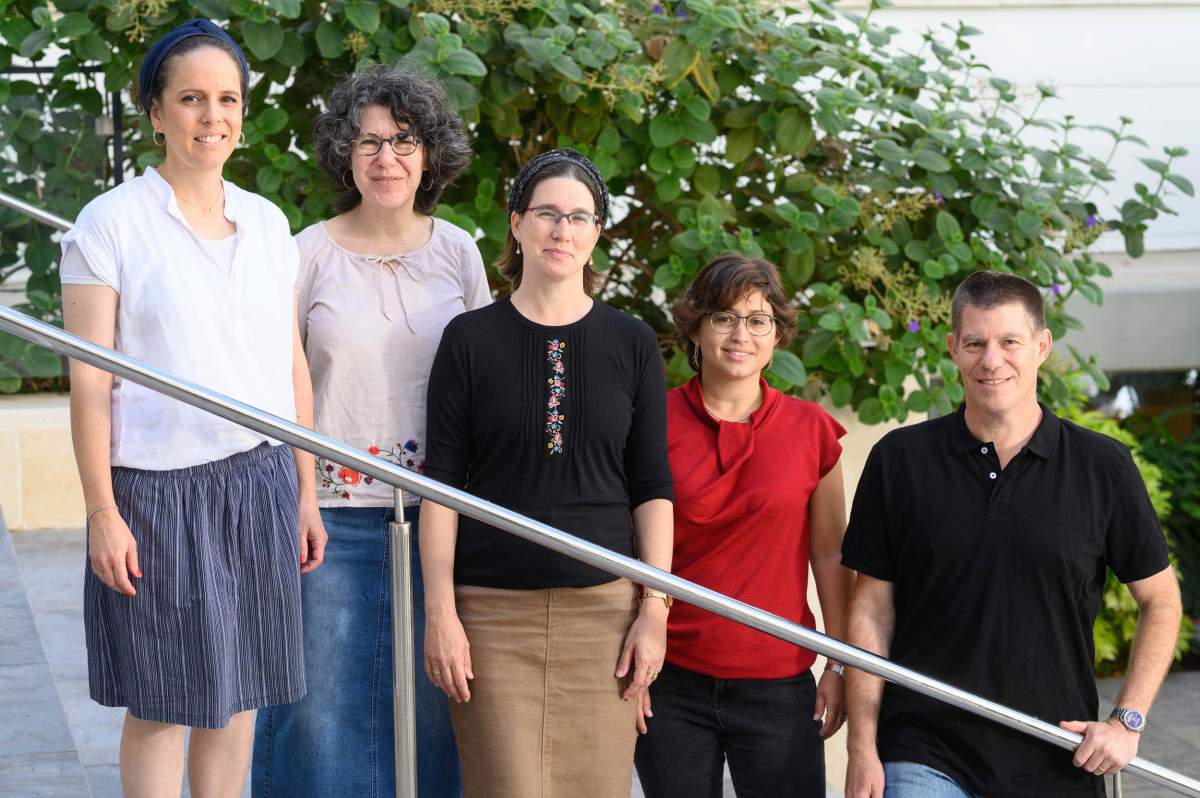

(l-r) Dr Deborah Nejman, Dr Nancy Gavert, Dr Ilana Livyatan, Dr Lian Narunsky Haziza and Professor Ravid Straussman

Fungi (pink) inside the cells of a human ovarian tumor (cell nuclei are in blue). Image credit: Deborah Nejman and Nancy Gavert

An uncommon example of fungi (black) that are present in human lung cancer tissue (turquoise) but not inside the cells. Image credit: Lian Narunsky Haziza and Nancy Gavert