March 6, 2017

The motion of an object after being hit depends to a large extent on its shape: A round ball will spin very differently from an elongated baton. Spinning molecules also come in different shapes, although they are never truly round.

Professor Edvardas Narevicius and his group in the Weizmann Institute of Science’s Chemical Physics Department have demonstrated that at very low temperatures – less than a hair above absolute zero – one can hit molecules and get them to behave either like balls or like batons – depending on certain initial conditions.

The findings, which appeared in Nature Physics, provide proof of a conjecture in quantum mechanics, and they could have implications for both chemistry and physics experimental setups.

Collisions between atoms and molecules occur all around us and they are necessary for most chemical reactions. But to truly understand the interaction, scientists look to the quantum realm.

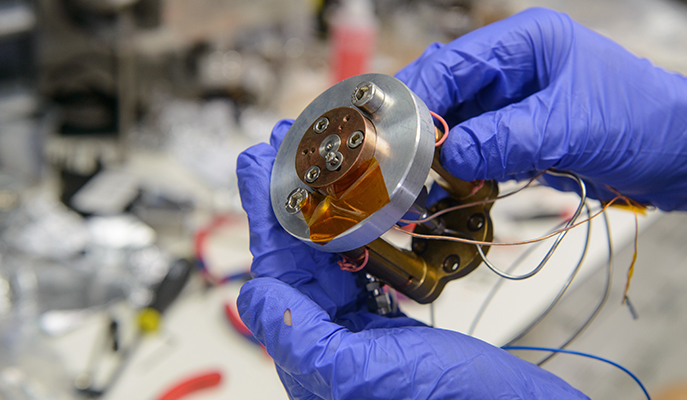

Narevicius and his laboratory group have created a unique setup for this, in which atoms or molecules are cooled down to ultracold temperatures – sometimes under 1⁰ Kelvin (K) – and collisions are created by merging parallel beams. This method eliminates a problem in many collision experiments that have particles colliding at high velocities relative to one another, so that the resulting high collision energies mask the fine quantum effects.

In the experiment, the researchers decided to address the issue of collisions with molecules. Atomic collisions have been studied, but atoms, as far as classical physics are concerned, are balls. Molecules, on the other hand, can be more like batons, and differences of shape should change collision properties. The simplest of these is hydrogen (H2), which consists of only two bound atoms. Would the stick-like molecules react differently to collisions than round atoms? Can one predict the outcome of a collision on the basis of shape?

Narevicius explained that as opposed to classical physics, in which objects at rest can be fully described by their shape, in quantum mechanics, atoms, molecules and their electrons are in constant motion even at the lowest energies – close to absolute zero.

The outcome of a collision will depend not only on shape but also on orientation, which in quantum mechanics cannot be defined but has rather to be understood as a set of possibilities. One must analyse the distribution of these possibilities to understand the ‘shape’ of a molecule. Also trying to probe interactions in the quantum world presents other difficulties: Due to the weirdness of quantum mechanics, one cannot directly follow the act of an atom hitting the molecule as one would be able to observe, say, the motion of billiard balls on a table.

“Fortunately, we have a wonderful handle that can help us observe what happens in these situations. In previous research we showed that there is a very narrow, ultracold temperature range in which you get much higher reaction rates than normal. This is the place where particles, rather than bouncing off the molecule, tunnel through a barrier and thus increase the probability that the reaction will take place. And we are practically the only lab in the world that can see when there has been this sort of change due to a collision,” said Narevicius.

Narevicius and his team, including Ayelet Klein and Yuval Shagam, together with their theory colleagues Dr Wojciech Skomorowski and Professor Christine Koch of Kassel University, Germany, ran and theoretically analyzed two collision experiments.

In one experiment, the molecules were in a so-called ground state. That is, their rotational energy was as low as it could go. In the other, they were in an ‘excited’ state. In both, the team measured the spectrum-like collision patterns between the hydrogen molecules and helium atoms, looking for evidence of differences between the collisions – that is, signs that rather than always reacting in the same way, as a kicked ball would, there would a range of reactions, as if a baton were hit. In particular, they looked for the changes in the reaction rate indicating that tunneling became important for a reaction to proceed.

The researchers conducted both experiments at a range of temperatures: from room temperature down to a few millikelvins – just thousandths of a degree above absolute zero. For most of that range – down to 1⁰ K – all of the molecules behaved like spheres.

“They were indistinguishable from atoms, but once the experiment entered the millikelvin range, interesting things began to happen,” said Narevicius.

The molecules in the ground-state rotational energy continued their sphere-like behaviour in the collisions, but the excited ones changed their behaviour and reacted as sticks would. The measurements of these collisions revealed a peak – a narrow temperature range in which tunneling was taking place in some of them. Only rotationally-excited molecules participated in such tunneling-driven reactions.

“Simple molecules in the ground rotational state are perfectly symmetrical, like atoms,” said Narevicius.

“Exciting them causes them to break that symmetry and show their real, elongated shape. By controlling the state of the molecule, you can create a switch – atom to molecule, ball to baton.”

Narevicus and his group now plan to expand their experiment from investigating single collisions to those in many-body setups. Experiments in which a large number of molecules will be held in ultracold, identical states, or ‘condensates’, are expected to open new possibilities for investigating the laws of physics.

The findings of the present experiment suggest that the nature and strength of interactions between molecules can be dramatically controlled by changing the rotational molecular state.

The research of Professor Edvardas Narevicius is supported by the Benoziyo Endowment Fund for the Advancement of Science and the Helen and Martin Kimmel Award for Innovative Investigation.

Professor Edvardas Narevicius showed that one can control the shapes of colliding molecules

The Even-Lavie supersonic valve developed at the Tel-Aviv University, is the source of cold atoms and molecules in the experiments