December 18, 2019

One day ‘blue blood’ might be synonymous with a way to help the heart heal. Researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science found that a non-toxic blue dye used in biology labs can help repair damaged heart tissue in mice. The results of this research were recently published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation (JCI) Insight.

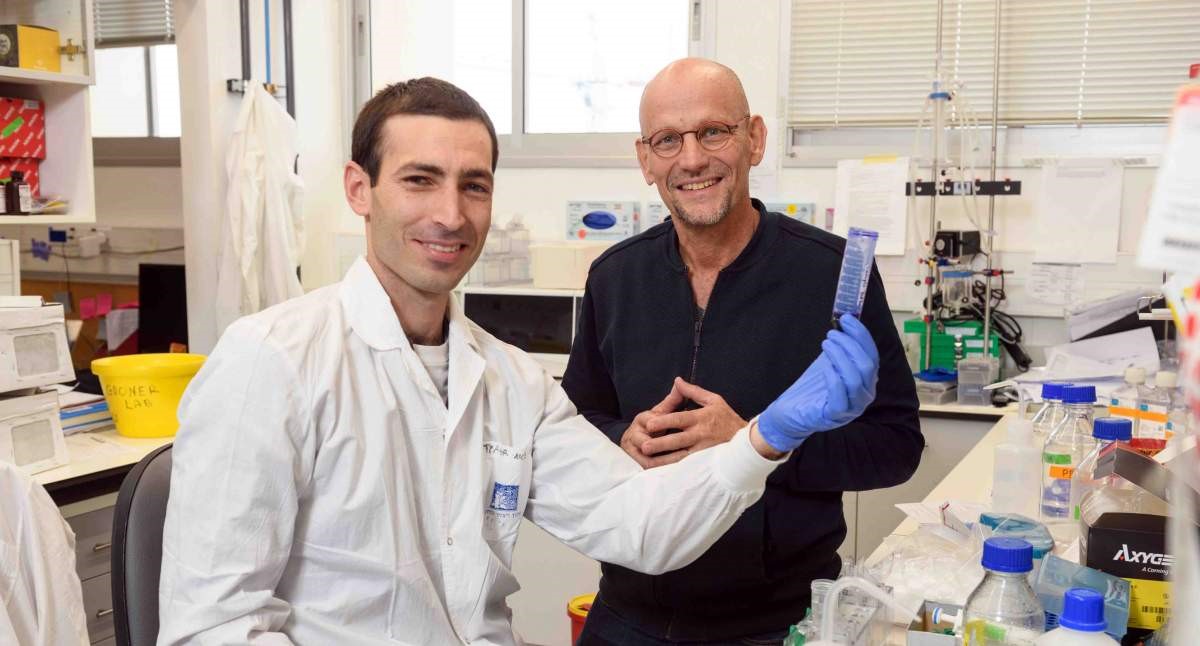

The research began several years ago when Professor Eldad Tzahor’s group in the Institute’s Molecular Cell Biology Department was growing heart muscle cells, called cardiomyocytes, in a laboratory dish.

Hoping to identify potential drugs that could renew damaged heart cells or get new ones to grow, the scientists teamed up with Dr Haim Barr and Noga Kozer in the high-throughput drug discovery unit in the Nancy and Stephen Grand Israel National Center for Personalized Medicine (G-INCPM), on the Weizmann campus. Using the robotic equipment there, the team members placed cardiomyocytes in tiny wells, adding a thousands of different small molecules, one to each well. Such small molecules – biochemical compounds – are favoured for drug development as they are cheap, stable, and immuno-tolerable.

The cells were tracked over six days and their numbers tallied. At the end of the trial, one compound was seen to cause the cardiomyocyte numbers to increase rather than stagnate or die off: This was a molecule known as Chicago Sky Blue (describing the exact shade over the city on a clear day, shortened to CSB). This dye is commonly used for research and diagnosis.

In the current study, the team took this molecule and tested it in real conditions, in mouse models of heart attack. In adult mice, as in humans, a heart attack causes scar tissue to form. Heart cells – which are strong enough to keep working continuously for decades – do not regenerate, thus when damage occurs it is normally irreversible. Led by research student Oren Yifa in Tzahor’s lab, the team injected the blue dye in the hearts of mice following injury and found their heart function was improved. Heartened by this finding, the team looked in these mice for evidence of heart cell renewal – but they found none.

How was CSB helping the hearts regain function if it was not replacing damaged cells?

The team hypothesized that it might suppress certain kinds of inflammation. Inflammation, explains Tzahor, is the body’s response to injury, but too much inflammation can cause cells in the heart called fibroblasts to continue producing scar tissue, and this can become a vicious cycle that brings further deterioration.

When the researchers looked at hearts after treatment with CSB, they found less scarring than in control counterparts, and the hearts of these mice did not become dilated, blowing up like balloons, as often happens after injury to the heart.

The team discovered that CSB prevents the activation of immune cells called macrophages. These cells are active in the process of wound healing, but in the heart, this healing can be tied to scar tissue formation after a heart attack. Treatment with CSB after cardiac injury resulted in fewer activated macrophages; and this drop in activation was linked to less scarring than in the hearts of control mice.

Further investigation suggested the dye works in two ways: In addition to reducing inflammation, it inhibits the actions of an enzyme known as CaMKII, which is overproduced in heart disease. Over-activation of this enzyme following heart injury impairs the crucial process of calcium handling in cardiomyocytes, and this in turn impairs contraction.

The researchers found that the CSB dye inhibits the activation of this enzyme, hinting at the possibility of improving heart contractility. When they experimented with special lab-grown, engineered heart tissue – ‘cardiobundles’ created in the lab of Professor Nenad Bursac in Duke University – they found that CSB indeed appeared to increase cardiomyocyte contraction.

“In my lab, most of the time we focus on finding drugs that can promote cardiomyocyte renewal,” said Tzahor.

“This research showed us that we also need to pay attention to other processes that take place following a heart attack, including inflammation and impairment in contractility. Because Chicago Sky Blue is non-toxic, we think it might be tested to prevent further damage following the initial injury of a heart attack.”

A new partnership for heart regeneration

Professor Eldad Tzahor and his team recently partnered with 10 other groups across Europe in an ambitious project to understand the process of heart cell renewal and to bring these findings to the clinic.

This project, called REANIMA, will receive some €8 million over five years from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program.

The project is led by Professor Miguel Torres, of the Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC), in Spain, and it includes researchers from Germany, the UK, Switzerland, Italy, Austria and the Netherlands. More importantly, said Tzahor, the partnership is structured so that at one end of the research are groups investigating heart cell renewal in animals like fish and salamanders that can regenerate all their body parts, through labs like Tzahor’s that investigates the process in mice, up to labs that apply the insights from mice to large animals with hearts closer to those of humans (mostly pigs) and ultimately to clinical research.

While the main labs involved, at this point, are academic, some of the partners are pharmaceutical and biotech companies that will help bridge the gap between lab bench and clinic.

“Our lab here at the Weizmann Institute of Science is pivotal to this program,“ said Tzahor.

“A significant part of the REANIMA project will focus on two of the molecules we discovered, both of which appear to be crucial to reversing the mammalian heart’s refusal to regenerate.”

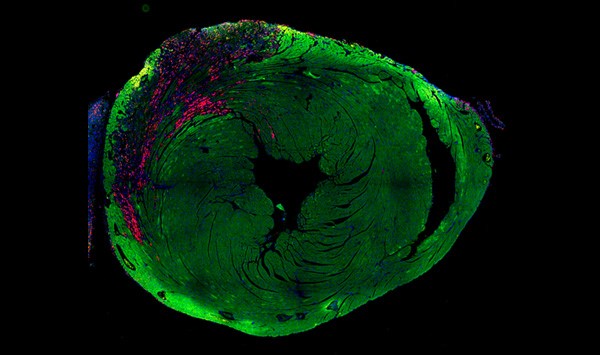

Injured heart following myocardial infarction. Red staining marks the immune cells in the injured zone

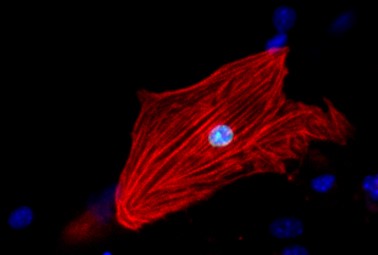

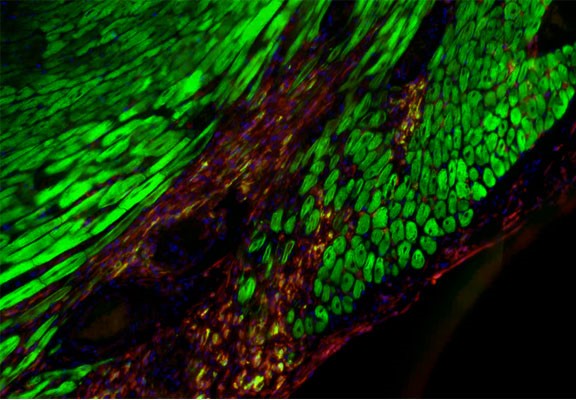

Cardiomyocyte: Red is the contractile fibers, blue the nucleus, green a proliferation marker. When the cardiomyocytes mature, the expression of proliferation markers in the nucleus does not necessarily leads to true cell proliferation

Injured heart following myocardial infarction. Healthy cardiomyocytes are stained in green. Injured area is stained in red.

Oren Yifa and Professor Eldad Tzahor