November 3, 2017

In the 1880s, Russian zoologist EIie Metchnikoff invented the term macrophage – meaning ‘big eater’ – for a certain type of white blood cell, due to the way it devours and digests cellular debris and foreign particles as part of the body’s immune defence.

Now Professor Steffen Jung and his colleagues in the Weizmann Institute of Science’s Immunology Department have added a new take on these cells, with recent findings showing that macrophages also inadvertently play a role in obesity.

The new research also shows these immune cells are crucial to maintaining harmony, including that of heat-producing fat cells.

Jung initially set out to investigate Rett syndrome – a rare neurological disorder of the brain. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in a gene called MECP2, whose protein product is found in all cells of the body and is essential for the normal functioning of the nerves.

Having studied macrophages for over a decade, Jung wondered whether mutations to the genes in these cells might contribute to the disorder.

However, when the scientists in Jung’s lab, including former PhD student Dr Yochai Wolf and Staff Scientist Dr Sigalit Boura-Halfon mutated this gene in macrophages in mice, it did not lead to Rett syndrome. Instead, the mice surprisingly gained weight and developed spontaneous obesity.

“Obesity can occur for different reasons – say excessive eating or the lowered burning of energy. It was not immediately clear why these particular mice were obese,” said Jung.

To find out why, the scientists established two experimental models that allowed them to mutate the MECP2 gene in macrophages of either newborn or adult mice; they then compared them to control groups in which the gene was kept intact.

Although all animals were fed the same food, only the groups whose genes were mutated gained excessive weight.

The fact that both of the newborn and adult mouse models became obese suggested that it was not a developmental issue.

With the help of Dr Yael Kuperman of the Veterinary Resources Department and her specialised experimental setup, abnormal food intake was also excluded as a cause. The researcher observed, however, that the mutated mice produced less heat.

A faulty thermostat

This observation led the scientists to investigate brown adipose tissue (BAT) – or brown fat.

BAT allows the body to maintain its internal core temperature in a balanced state, as it is responsible for the ‘non-shivering’ heat production in which the energy derived from food is converted into heat. Indeed, when the gene was mutated, Jung and his team saw a reduction in the level of activity of a protein called UCP1, which has the task of overseeing the heat production in BAT. Along with this impairment in heat production and the subsequent reduced energy expenditure, the scientists observed a profound accumulation of fat.

The scientists then sought to reveal the cause of the drop in UCP1 levels in these mice. In normal conditions, UCP1 production is triggered by the release of the hormone norepinephrine, which is transmitted through the long, slender projections of nerve cells called axons. They found that there was a reduced number of these axons in the BAT of mutated mice.

BAT loses its nerve

By performing a more detailed gene expression analysis the scientists revealed that the production of an ‘axon guidance’ protein called Plexin A4 was increased in mutated mice.

Turning to Professor Avraham Yaron of the Biomolecular Sciences Department, who has conducted extensive research on this protein and could provide valuable advice and additional research tools, the scientists put forward a plausible explanation as to the molecular mechanisms leading to obesity. Their findings were published in Nature Immunology.

Macrophages deficient in MECP2 overexpress Plexin A4, according to this proposal. Because Plexin A4 keeps the nervous system orderly, its overactive signals to the nerve axons suppress their growth in BAT. The resulting decrease in nerves thus lowers the transmission of the critical norepinephrine signal required to trigger UCP1 activity in the brown fat cells. Consequently, less heat is produced and energy expenditure is reduced, ultimately leading to obesity.

From ‘big eaters’ to ‘balancers’

Jung: “These results are exciting, as macrophages are renowned for the role they play in the immune system: clearing damaged and dying cells, and fighting off infection. But now we have identified a new homeostatic role for macrophages in maintaining a healthy balanced state by controlling the innervation of BAT to ensure normal heat production.

“Although our mutated model produces a very subtle change – i.e., only reduced innervation of BAT, without the inflammation or ingestion of unwarranted cells that usually accompany macrophage activity – the change causes a profound and unexpected effect: obesity.”

This new role for macrophages adds to recent findings showing that macrophages residing in other tissues and organs are vital to the homeostatic function of a number of biological systems.

Professor Steffen Jung’s research is supported by the Belle S. and Irving E. Meller Center for the Biology of Aging, which he heads; the Kleinman Cancer Cell Sorting Facility; the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust; and the Maurice and Vivienne Wohl Biology Endowment.

(l-r) Dr. Yochai Wolf, Prof. Steffen Jung and Dr. Sigalit Boura-Halfon found a surprising connection between immune cells and weight gain

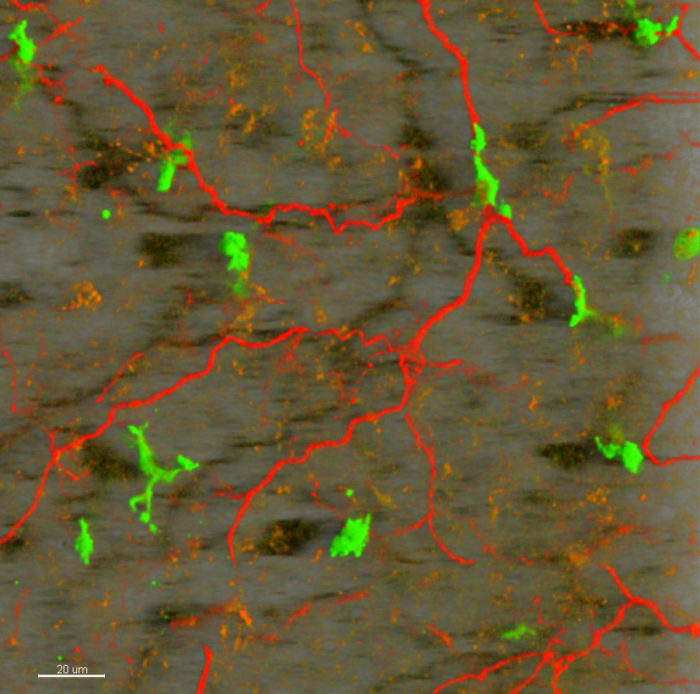

Characterisation of macrophages (green) and axons (red) in brown adipose tissue (BAT) using two-photon fluorescence microscopy imaging