December 15, 2017

Global efforts to eradicate malaria are dependent on scientists’ ability to outsmart the malaria parasite and a new study suggests a possible defence in the battle against this disease.

Plasmodium falciparum – the parasite that causes malaria – is notoriously clever: It is quick to develop resistance against medications and has such a complex life cycle that blocking it effectively with a vaccine has thus far proved elusive.

The new study, reported in Nature Communications, from researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science and others in Ireland and Australia, showed that Plasmodium falciparum is even more devious than previously thought: Not only does it hide from the body’s immune defences, it employs an active strategy to deceive the immune system.

Among transmittable diseases, malaria is second only to tuberculosis in the number of victims, putting at risk nearly half of Earth’s population. More than 200 million people become infected every year; about half a million die, most of them children under five years of age.

“Malaria is one of the world’s most devastating diseases – it’s a true bane of low-income countries, where it kills a thousand young children every day,” said Dr Neta Regev-Rudzki of Weizmann’s Biomolecular Sciences Department.

“To fight malaria, we need to understand the basic biology of Plasmodium falciparum and figure out what makes it such a dangerous killer.”

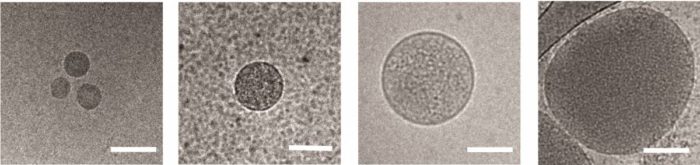

Regev-Rudzki had previously discovered, in her postdoctoral studies in the laboratory of Professor Alan Cowman at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research in Melbourne, Australia, that these parasites communicate with one another while in the incubation stage in the blood. They do so by releasing sac-like nanovesicles – less than 1 micron across – that contain small segments of the parasite’s DNA. Apparently these signals help the parasites learn when it’s time to start transforming into male and female forms, both of which can be carried by mosquitoes into new hosts. This finding was all the more startling because the nanovesicles need to cross six separate membranes to communicate the message from a parasite inside one red blood cell to another.

In the new study, performed in collaboration with Professor Andrew G. Bowie of Trinity College Dublin and other researchers, Regev-Rudzki and her Weizmann team discovered that in parallel with communicating with other parasites, Plasmodium falciparum uses this same communication channel for yet another purpose: to deliver a misleading message to the infected person’s immune system.

Within the first 12 hours after infecting red blood cells, the parasites send out DNA-filled nanovesicles that penetrate cells called monocytes. Normally, monocytes form the immune system’s first line of defense against foreign invasion, sensing danger from afar and alerting other immune mechanisms to mount an effective response. Naturally, the immune system dispatches its next line of defence to these cells.

But in fact, the nanovesicles have converted the monocytes into decoys. While the immune system is busy defending the organism against fake danger, the real infection proceeds inside red blood cells, allowing the parasite to multiply unhindered at dizzying speed. By the time the immune system discovers its mistake, precious time has been lost, and the infection is much more difficult to contain.

Regev-Rudzki’s team has identified a key molecular sensor, a protein called STING that becomes activated when the parasite’s nanovesicles penetrate monocytes. It is STING that delivers the fake alert to the immune system, tricking it into ‘thinking’ that its monocytes are in danger. When the scientists ‘knocked out’ the gene that manufactures STING, the chain of molecular reactions generating the misleading alert was interrupted.

“We’ve discovered a subversive strategy the malaria parasite employs in order to thrive in human blood. By interfering with this subversion of the immune system, it may be possible in the future to develop ways of blocking malarial infection,” said Regev-Rudzki.

The research team included Dr Yifat Ofir-Birin, Paula Abou Karam and Tal Giladi of Weizmann’s Biomolecular Sciences Department; Dr Ziv Porat of Weizmann’s Life Sciences Core Facilities Department; Dr Xavier Sisquella, Matthew A. Pimentel, Dr Natália G. Sampaio, Jocelyn Sietsma Penington, Dr Andreea Waltmann, Professor Louis Schofield, Dr Diana S. Hansen, Professor Anthony T. Papenfuss and Dr. Emily M. Eriksson of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Melbourne, Australia; Dr Lesley Cheng, Dr Benjamin J Scicluna, Robyn A. Sharples and Professor Andrew F. Hill of the University of Melbourne and La Trobe University in Victoria, Australia; Dr Dympna Connolly and Professor Bowie of Trinity College Dublin, Ireland; Dr Dror Avni and Professor Eli Schwartz of the Sheba Medical Center at Tel Hashomer, Israel; and Dr Motti Gerlic of Tel Aviv University.

Dr Neta Regev-Rudski’s research is supported by David E. and Sheri Stone; the Weizmann – UK Making Connections Program; and the European Research Council. Dr Regev-Rudski is the incumbent of the Enid Barden and Aaron J. Jade President’s Development Chair for New Scientists in Memory of Cantor John Y. Jade.

Nanovesicles released from red blood cells infected by Plasmodium falciparum, viewed under an electron microscope. Scale bar: 100 nm

A monocyte converted into a decoy by the malaria parasite: The green dot is the genetic material “cargo” inside the nanovesicle produced by the parasite