July 13, 2021

New research from the Weizmann Institute of Research shows that changes to the extracellular matrix could point to the future development of inflammatory bowel diseases.

The morbidity rate of inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis is steadily on the rise in developed countries.

Despite the progress that has been made in our ability to treat such illnesses, patients suffering mild to severe symptoms are still regularly in and out of hospitals and at greater risk for developing colon cancer. Scientists from the

Weizmann’s recently discovery reveals that the onset of inflammation can be anticipated by observing changes to the extracellular matrix – the three-dimensional scaffolding network, composed mostly of proteins and carbohydrates, that surrounds cells in various tissues. These findings could assist in the early detection of inflammatory bowel diseases and pave the way for the development of improved therapeutics.

The pioneering work of Professor Irit Sagi’s group at Weizmann’s Biological Regulation Department joins that of other research groups around the world in highlighting the central role of the extracellular matrix in the pathogenesis of a variety of diseases, from flu to cancer.

Similarly to other tissues, the gastrointestinal tract also consists of an extracellular matrix that provides both structural and biochemical support to its constituent cells.

The extracellular matrix is in fact a key player in the tissue’s overall structural stability and normal functionality. During inflammation, extreme structural changes often occur to both the intestine and the extracellular matrix. These may lead to the development of medical complications such as fibrostenosis – persisting tissue injury that results in narrowing of the intestine – or fistulas, which are abnormal passageways that form between two different organs. Unfortunately, in many cases these complications cannot be avoided or medicinally treated, and physicians often have to resort to surgery and other invasive procedures.

For many years the working assumption was that once inflammation has developed it will ultimately lead to damage to the extracellular matrix. In other words, structural changes to the extracellular matrix were believed to be mere side effects of inflammation that occur at a relatively late stage of the disease.

This assumption was recently turned on its head following the results of a study conducted by Sagi’s group, led by now-former member Dr Elee Shimshoni. Shimshoni, together with colleagues from the Weizmann Institute of Science, and other researchers from the Sackler School of Medicine at Tel Aviv University and the Sheba and Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Centers, demonstrated that changes to the extracellular matrix happen much earlier in the disease’s progression, even before clinical manifestations can be detected by standard medical procedures such as a colonoscopy or biopsy.

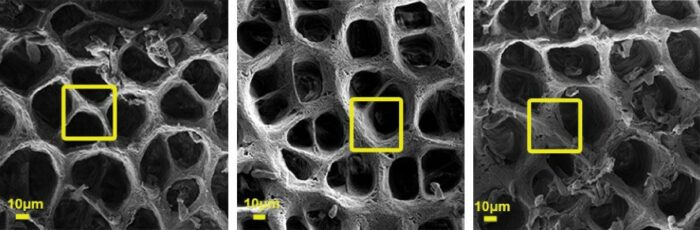

“We discovered that the pre-symptomatic extracellular matrix has a unique signature that differentiates it from the extracellular matrix of a healthy intestine: it is less stiff, has a different composition of proteins, and displays an overall altered structure,” said Shimshoni.

The team of researchers studied two different colitis mouse models in their work, and despite the mechanistic differences between the two, they were surprised to discover that the pre-symptomatic signature was very similar in both.

One of the most noticeable characteristics of this signature was the apparent damage to the intestinal basement membrane (basal lamina) – a dense, ‘mesh-like’ type of extracellular matrix that provides structural tissue support; damage to this membrane – one of the layers providing a partition between the intestine’s internal and external environments – exposes the immune system to resident gut bacteria, which could initiate inflammation.

The study revealed that a small number of neutrophils – first-response immune cells that help heal tissue damage – were indeed already present in the pre-symptomatic state. These cells, despite their small numbers, can recruit a variety of protein-degrading enzymes that dismantle the extracellular matrix in general, and the basement membrane in particular.

“As opposed to the popular approach, which states that changes to the extracellular matrix are merely late by-products of inflammation, our study suggests that these changes in fact take place parallel to the course of disease and even contribute to its progression,” saod Sagi.

“We hypothesise that the combination between initial damage to the extracellular matrix and the arrival of first-response immune cells opens a gateway for other immune cells to join, and facilitates the onset of inflammation.”

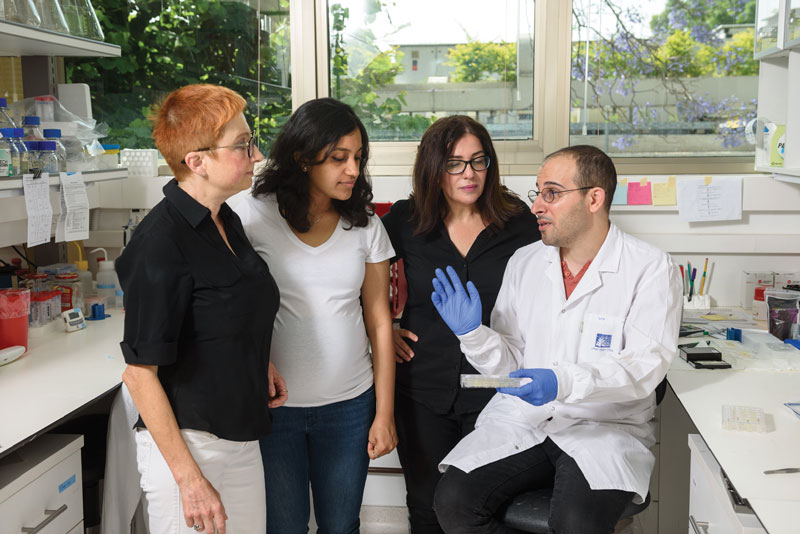

(l-r) Dr Inna Solomonov, Dr Anjana Shenoy, Professor Irit Sagi and Idan Adir. Reading the signs

The extracellular matrix as captured by a scanning electron microscope (SEM). Left: Healthy extracellular matrix, Right: Changes to the extracellular matrix that were observed in two different colitis mouse models

Dr Elee Shimshoni who led the study in Professor Irit Sagi's group