March 20, 2021

Cancer immunotherapy may get a boost from an unexpected direction: bacteria residing within tumour cells.

In a new study published in Nature, researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science and their collaborators have discovered that the immune system ‘sees’ these bacteria and shown they can be harnessed to provoke an immune reaction against the tumour.

The study may also help clarify the connection between immunotherapy and the gut microbiome, explaining the findings of previous research that the microbiome affects the success of immunotherapy.

Immunotherapy treatments of the past decade or so have dramatically improved recovery rates from certain cancers, particularly malignant melanoma; but in melanoma, they still work in only about 40% of the cases.

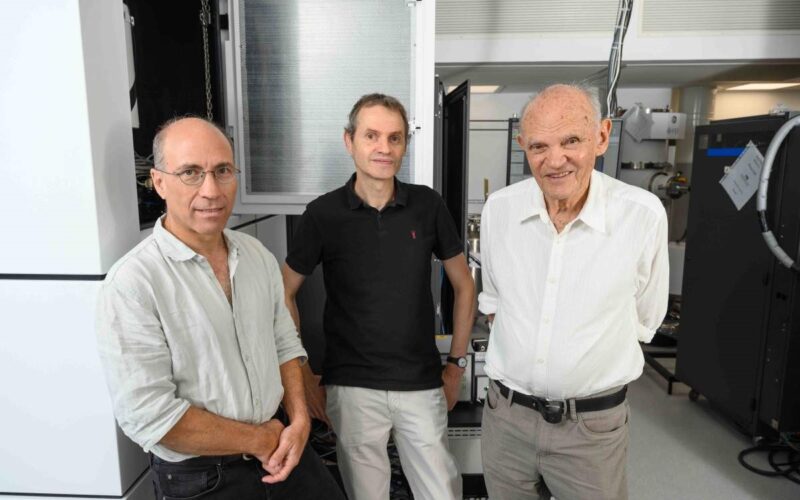

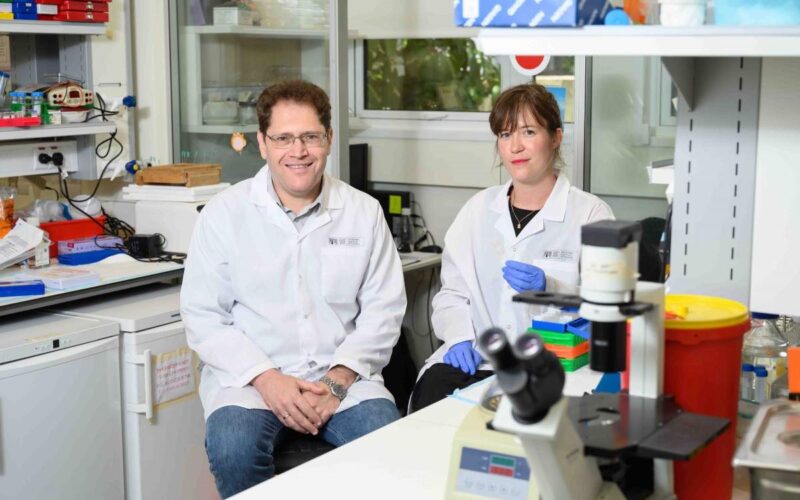

Professor Yardena Samuels of Weizmann’s Molecular Cell Biology Department studies molecular said ‘signposts’ – protein fragments, or peptides, on the cell surface – mark cancer cells as foreign and may therefore serve as potential added targets for immunotherapy. In the new study, she and colleagues extended their search for new cancer signposts to those bacteria known to colonise tumours.

Using methods developed by departmental colleague Dr Ravid Straussman, who was one of the first to reveal the nature of the bacterial ‘guests’ in cancer cells, Samuels and her team, led by Dr Shelly Kalaora and Adi Nagler (joint co-first authors), analysed tissue samples from 17 metastatic melanoma tumours derived from nine patients.

They obtained bacterial genomic profiles of these tumours and then applied an approach known as HLA-peptidomics to identify tumour peptides that can be recognized by the immune system.

The research was conducted in collaboration with Dr Jennifer A. Wargo of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas; Professor Scott N. Peterson of Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute, La Jolla, California; Professor Eytan Ruppin of the National Cancer Institute, USA; Prof Arie Admon of the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology and other scientists.

The HLA-peptidomics analysis revealed nearly 300 peptides from 41 different bacteria on the surface of the melanoma cells. The crucial new finding was that the peptides were displayed on the cancer cell surfaces by HLA protein complexes – complexes that are present on the membranes of all cells in our body and play a role in regulating the immune response.

One of the HLA’s jobs is to sound an alarm about anything that’s foreign by ‘presenting’ foreign peptides to the immune system so that immune T cells can ‘see’ them.

“Using HLA-peptidomics, we were able to reveal the HLA-presented peptides of the tumour in an unbiased manner,” Kalaora said.

“This method has already enabled us in the past to identify tumour antigens that have shown promising results in clinical trials.”

It is unclear why cancer cells should perform a seemingly suicidal act of this sort: presenting bacterial peptides to the immune system, which can respond by destroying these cells. But whatever the reason, the fact that malignant cells do display these peptides in such a manner reveals an entirely new type of interaction between the immune system and the tumour.

This revelation supplies a potential explanation for how the gut microbiome affects immunotherapy. Some of the bacteria the team identified were known gut microbes. The presentation of the bacterial peptides on the surface of tumour cells is likely to play a role in the immune response, and future studies may establish which bacterial peptides enhance that immune response, enabling physicians to predict the success of immunotherapy and to tailor a personalized treatment accordingly.

Moreover, the fact that bacterial peptides on tumour cells are visible to the immune system can be exploited for enhancing immunotherapy.

“Many of these peptides were shared by different metastases from the same patient or by tumours from different patients, which suggests that they have a therapeutic potential and a potent ability to produce immune activation,” Nagler said.

In a series of continuing experiments, Samuels and colleagues incubated T cells from melanoma patients in a laboratory dish together with bacterial peptides derived from tumour cells of the same patient. The result: T cells were activated specifically toward the bacterial peptides.

“Our findings suggest that bacterial peptides presented on tumour cells can serve as potential targets for immunotherapy,” Samuels said.

“They may be exploited to help immune T cells recognize the tumour with greater precision, so that these cells can mount a better attack against the cancer. This approach can in the future be used in combination with existing immunotherapy drugs.”

Also participating in this research were, from the Weizmann Institute of Science: Dr Deborah Nejman, Dr Michal Alon, Chaya Barbolin, Dr Ronen Levy, Sophie Trabish, Dr Leore Geller, Polina Greenberg, Gal Yagel, Dr Aviyah Peri and Lior Roitman from Molecular Cell Biology Department; Yuval Bussi, Dr Adina Weinberger, Maya Lotan-Pompan and Professor Eran Segal from Computer Science and Applied Mathematics Department and Molecular Cell Biology Department; Dr Ron Rotkopf and Ofra Golani from Life Sciences Core Facilities Department; Dr Tali Dadosh and Dr Smadar Levin-Zaidman from Chemical Research Support Department; Dr Garold Fuks from Physics of Complex Systems Department; and Dr Raya Eilam from Veterinary Resources Department.

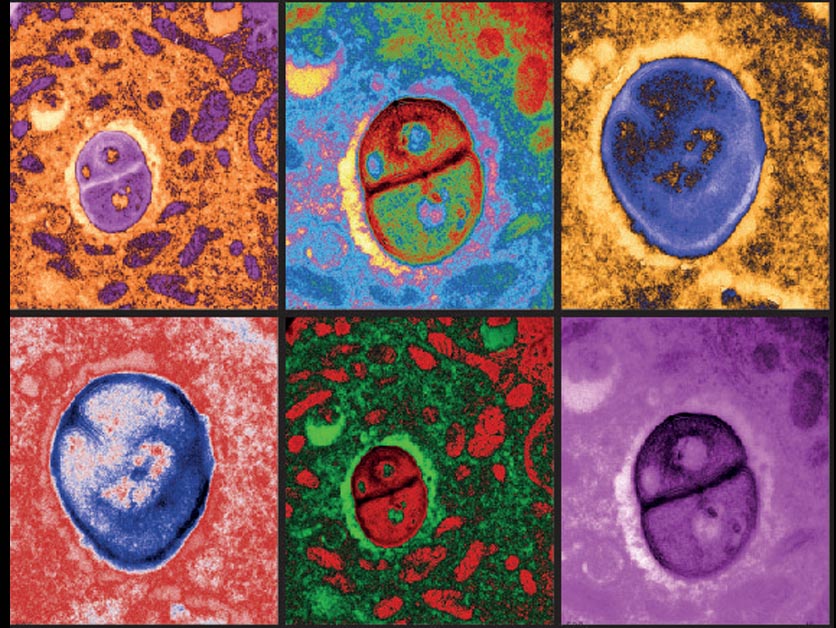

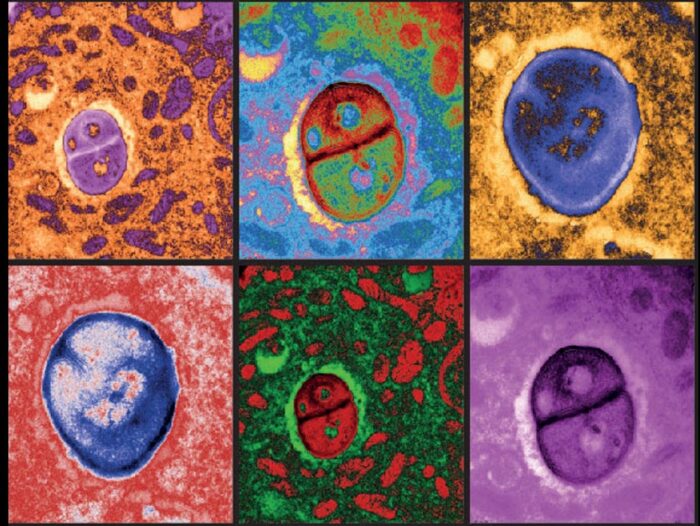

Digitally coloured electron microscopy images of melanoma cells harbouring bacteria

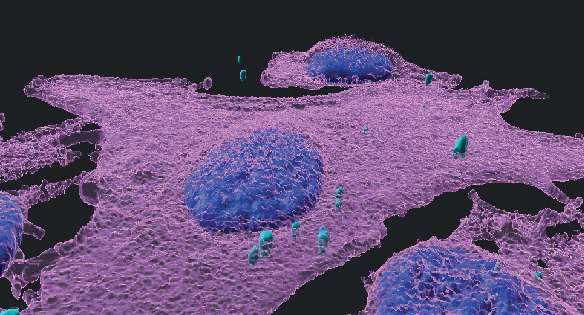

A 3D immunofluorescent image of melanoma cells (magenta) infected with bacteria (turquoise); cell nuclei are blue