September 17, 2024

Will a better understanding of photosynthesis help us grow plants under artificial light? New research at the Weizmann Institute of Science is looking to answer this question.

Photosynthesis, the process by which plants, algae and certain kinds of bacteria convert solar radiation into chemical energy, must adjust itself to changes in the intensity of sunlight, so as to ensure its efficient use. Just like our pupils, which react to varying degrees of light exposure with dilation or constriction, organelles in plant cells undergo changes in response to sunlight. But unlike ourselves, plants cannot avert their eyes or rest in the shade to avoid excessively intense sunlight; they must be able to cope with different levels of solar radiation, as well as with its absence at night.

Without photosynthesis, life as we know it on Earth would be impossible. Not only is this process responsible for generating most of the oxygen in Earth’s atmosphere, but it also secures food availability, sequesters carbon from the atmosphere and mitigates the effects of climate change. Understanding photosynthesis in all its intricacies is therefore crucial for dealing with the impending challenges facing our planet.

Research conducted in Professor Ziv Reich’s lab in the Weizmann Institute of Science’s Biomolecular Sciences Department aims to uncover the mysteries of photosynthesis so it can be used more efficiently to meet humanity’s needs or imitated by artificial methods that would mimic natural photosynthetic processes.

In photosynthesis, harnessing the power of the Sun is made possible by the flow of electrons from one protein to another inside an organelle called the chloroplast. This organelle contains a complex system of membranes, some of which are densely stacked, and others that are organised into more expansive assemblies. Until now, the scientific consensus was that this spatial structure forces the electrons to cover large distances between proteins, slowing down the process of photosynthesis.

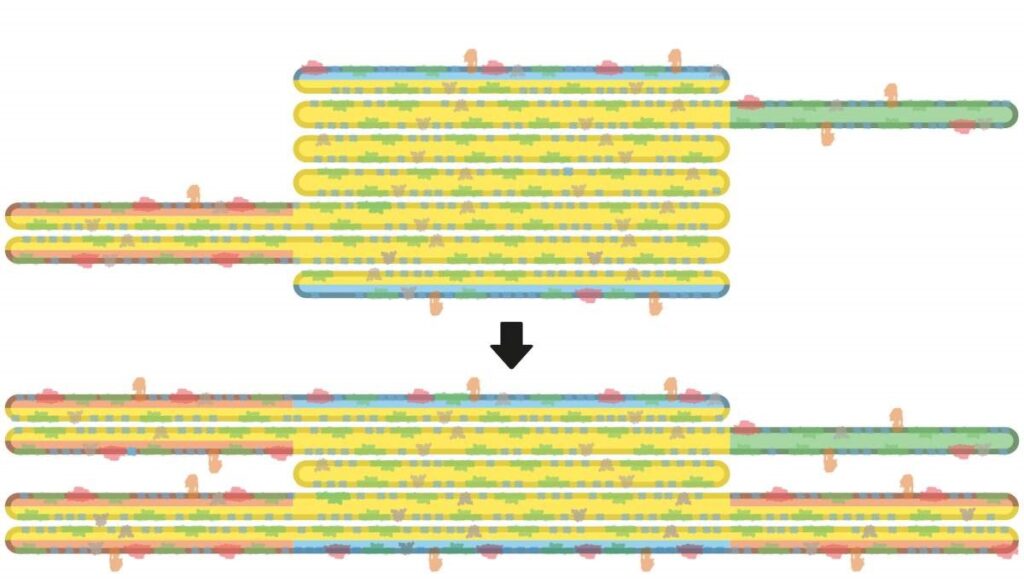

However, in a paper recently published in Nature Plants, a research team led by staff scientist Dr Reinat Nevo from Reich’s lab revealed that the membranes change their organisation in space during the transition from darkness to light, enabling the proteins to come closer to one another and thus shortening the distance the electrons must cross.

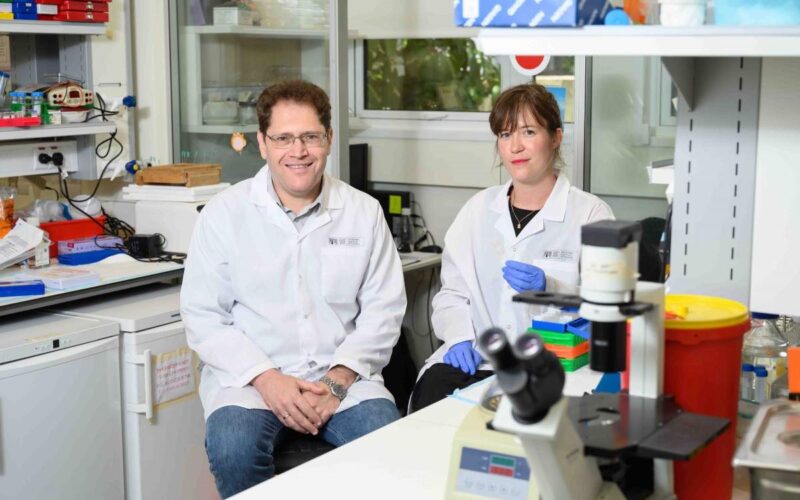

These revelations were made when the researchers examined the chloroplast membranes under a cryo-scanning electron microscope and compared the alignment of proteins in the membranes under both light and darkness conditions.

“When we looked into the protein density, we realised that the proteins themselves were not changing their positions, as previously thought – rather, the change occurred in the way the membranes were organised in space,” explained Nevo.

Further tests, this time using a transmission electron microscope, confirmed the researchers’ hypothesis and showed that membranes indeed rearrange themselves in space, bringing the proteins closer to one another. Apparently, one of the reasons that the proteins aren’t permanently in close proximity to one another – and that the membranes distance themselves from each other under darkness – is that the distancing protects the proteins by isolating them when the light is weak and little photosynthetic activity is taking place.

After discovering how membranes realign themselves according to light conditions, the research team conducted an experiment with two groups of genetically modified plants: one in which the spatial structure of the chloroplast membranes is “locked” in an active light and photosynthesis mode and another in which the membranes are organised in a perpetual darkness mode, preventing them from getting closer to one other. The plants in the first group grew larger and performed more photosynthesis compared to their dark-mode counterparts.

In the future, Nevo and her colleagues plan to investigate whether genetically engineered plants, in which the spatial structure of membranes is regulated, can be grown in relatively weak light. This could help conserve energy when cultivating plants under artificial light – a need that might be imposed by climate change.

This study is dedicated to the memory of Dr Eyal Shimoni, a staff scientist in Weizmann’s Chemical Research Support Department, who contributed essential expertise in microscopy to this research before he prematurely passed away in 2023.

Other participants included Dr Yuval Garty and Yuval Bussi of Reich’s group; Dr Smadar Levin-Zaidman of the Chemical Research Support Department; Professor Helmut Kirchhoff of Washington State University; and Dr Dana Charuvi of the Volcani Institute, Rishon LeZion, Israel.

(l-r) Dr Smadar Levin-Zaidman, Dr Yuval Garty, Dr Reinat Nevo, Yuval Bussi, Dr Dana Charuvi and Professor Ziv Reich

A cryo-scanning electron microscope image of a freeze-fractured chloroplast, cropped from the surrounding tissue, providing a view into the photosynthetic membranes and the protein complexes embedded within them

A diagram showing changes in the spatial structure of chloroplast membranes during the transition from darkness (top) to light (bottom)

The late Dr Eyal Shimoni