June 15, 2021

A study recently published in PNAS looks at an important chapter in our anthropological evolution and suggests that Homo sapiens and Neanderthals were far from strangers.

The Boker Tachtit archaeological excavation site in Israel’s central Negev desert, is a place that holds clues to one of the most important events in human history: the spread of modern humans, Homo sapiens, from Africa into Eurasia, and the subsequent demise of Neanderthal populations in the region.

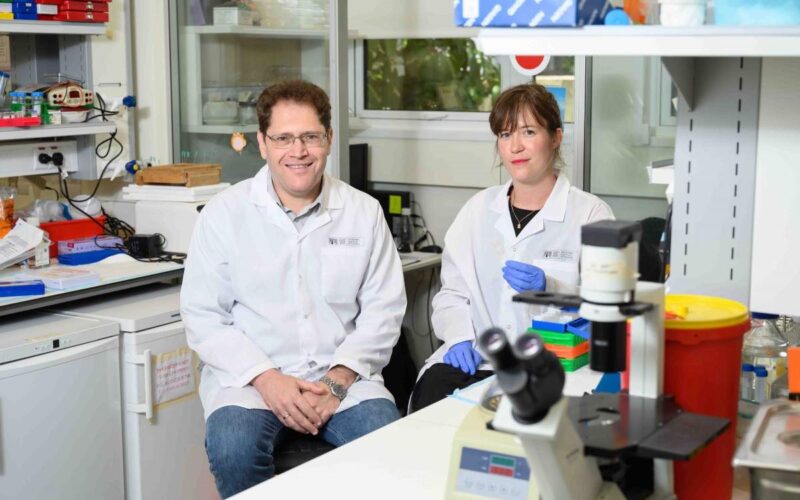

Researchers from the Weizmann Institute of Science and the Max Planck Society, led by Professor Elisabetta Boaretto, together with Dr Omry Barzilai of the Israel Antiquities Authority, returned to Boker Tachtit nearly 40 years after it was first excavated. Then using advanced sampling and dating methods, they found a new chronological framework that provided the revelation between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals.

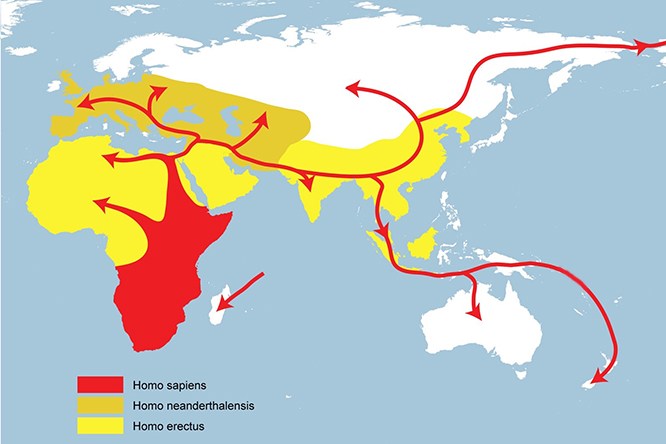

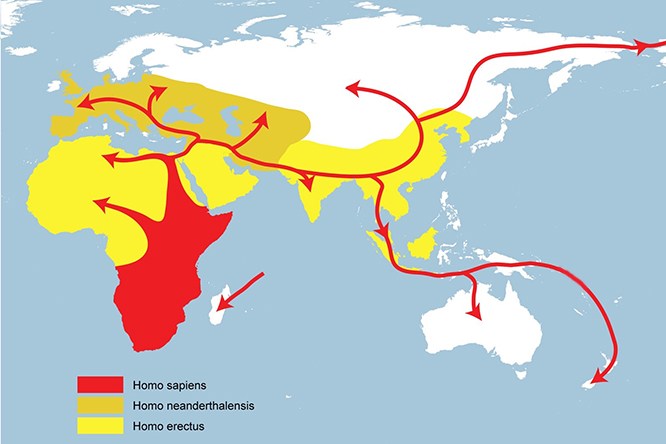

According to the ‘recent African origin’ theory, Homo sapiens originated in Africa as early as 270,000 years ago and at different times took either the northern route to Eurasia, passing through the Levant, or several possible southern routes to remote corners of Asia and even Oceania – reaching as far as Australia by land.

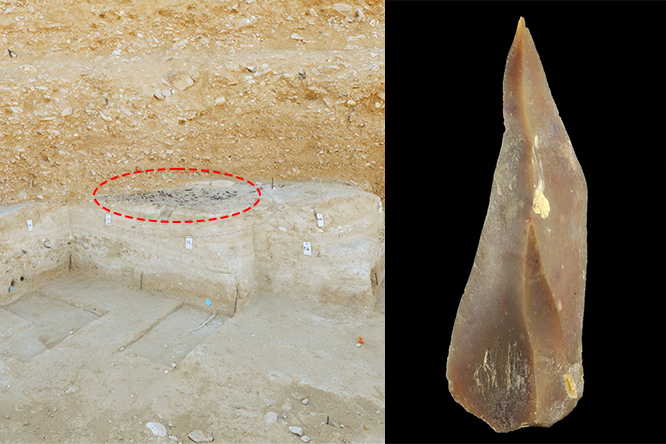

Boker Tachtit, located in the Wadi Zin basin, in what today is the Ein Avdat National Park, is considered a key site for tracing this migration. It is a major site in the Levant for documenting an important period in humankind’s prehistory: the transition from Middle to Upper Palaeolithic – from a predominantly Neanderthal prehistorical culture to the beginning of modern humans’ reign. This transition was marked by technological innovations such as blade production and the introduction of standardized tools made from bones and antlers.

American archaeologist Anthony Marks, who first excavated and published his analysis of Boker Tachtit in the early 1980s, defines the site as a transitional industry from the Middle to the Upper Palaeolithic and, based on a single radiocarbon date, concluded that it dates to 47,000 years ago. The problem was, however, that additional dates obtained from the site, some reaching as late as 34,000 years ago, made the timing of the transition very problematic.

“If we are to follow this timeline, then the transitional period could have lasted more than 10,000 years, and yet artefacts excavated from northern sites in Israel, Lebanon and even Turkey suggest that the transition occurred much faster,” said Boaretto, who heads D-REAMS – The Dangoor Research Accelerator Mass Spectrometry – Laboratory at the Weizmann Institute, which specialises in advanced archaeological dating methods.

“Marks managed to date only a few specimens from Boker Tachtit, owing to the limitations of radiocarbon dating then, and the range of his proposed dates is not consistent with evidence gathered from other – old and new – excavation sites in the region,” Boaretto said.

“Radiocarbon dating, the method that he used in his study, has evolved tremendously since his time.”

To resolve these questions, Boaretto, Barzilai and their multidisciplinary team performed advanced dating methods on specimens obtained from Boker Tachtit during the new excavations that they performed in 2013–2015. These included the latest techniques, such as high-resolution radiocarbon dating of single charcoal pieces found at the site and optically stimulated luminescence dating of quartz sand grains, performed at the Weizmann Institute and at the Max Planck Institute, respectively. The researchers also integrated detailed studies of the sediments, using micro archaeological methods to understand how the site was formed physically, contributing necessary data for the construction of its chronological framework.

“We are now able to conclude with greater confidence that the Middle-to-Upper Palaeolithic transition was a rather fast-evolving event that began at Boker Tachtit approximately 50-49,000 years ago and ended about 44,000 years ago,” Boaretto said.

This dating allows for a certain overlap between the material transition that occurred at Boker Tachtit and that of the Mediterranean woodland region (Lebanon, Turkey) between 49,000 and 46,000 years ago. Still, it shows that Boker Tachtit was the earliest site for this transition in the Levant, and that, based on the materials found, is a testimony to the last dispersal event of modern humans from Africa.

According to the new dating scheme, the early phase at Boker Tachtit also overlaps with the locally previous, Middle Palaeolithic culture in the region – that of the Neanderthals.

“This goes to show that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens in the Negev coexisted and most likely interacted with one another, resulting in not only genetic interbreeding, as is postulated by the ‘recent African origin’ theory, but also in cultural exchange,” Boaretto and Barzilai concluded.

Wadi Zin basin in the Ein Avdat National Park. Star indicating the location of Boker Tachtit

Depiction of the different routes that Homo sapiens migrated by according to the “recent African origin” theory. Adapted from Wikimedia Commons

Depiction of the different routes that Homo sapiens migrated by according to the “recent African origin” theory. Adapted from Wikimedia Commons