September 17, 2020

By tracking the evolution of what may be our oldest means of fighting off viral infection, a group at the Weizmann Institute of Science has uncovered a gold mine of antiviral substances that may lead to the development of highly effective antiviral drugs.

These substances are made by virus-fighting enzymes known as viperins, which were previously known to exist only in mammals, and have now been found in bacteria. The molecules produced by the bacterial viperins are currently undergoing testing against human viruses such as the influenza virus and COVID-19. The study was published today in Nature.

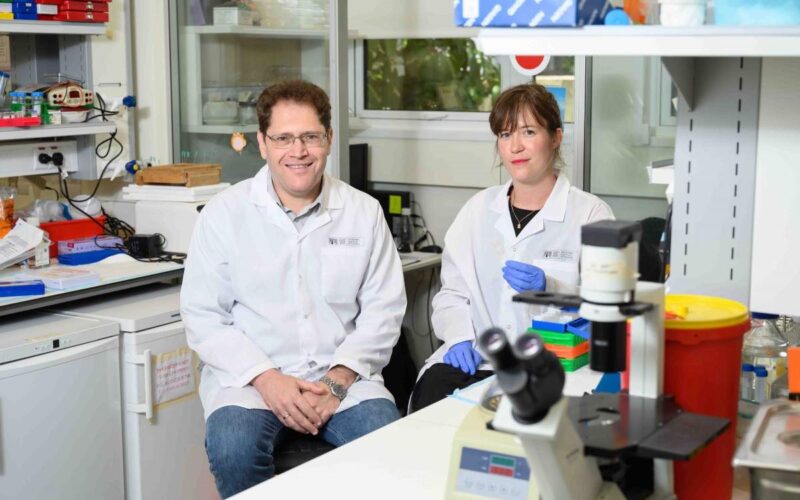

Studies conducted over the past decade by Professor Rotem Sorek and his group in the Institute’s Molecular Genetics Department, as well as those by other scientists, have revealed that bacteria have highly sophisticated immune systems, despite their microscopic size.

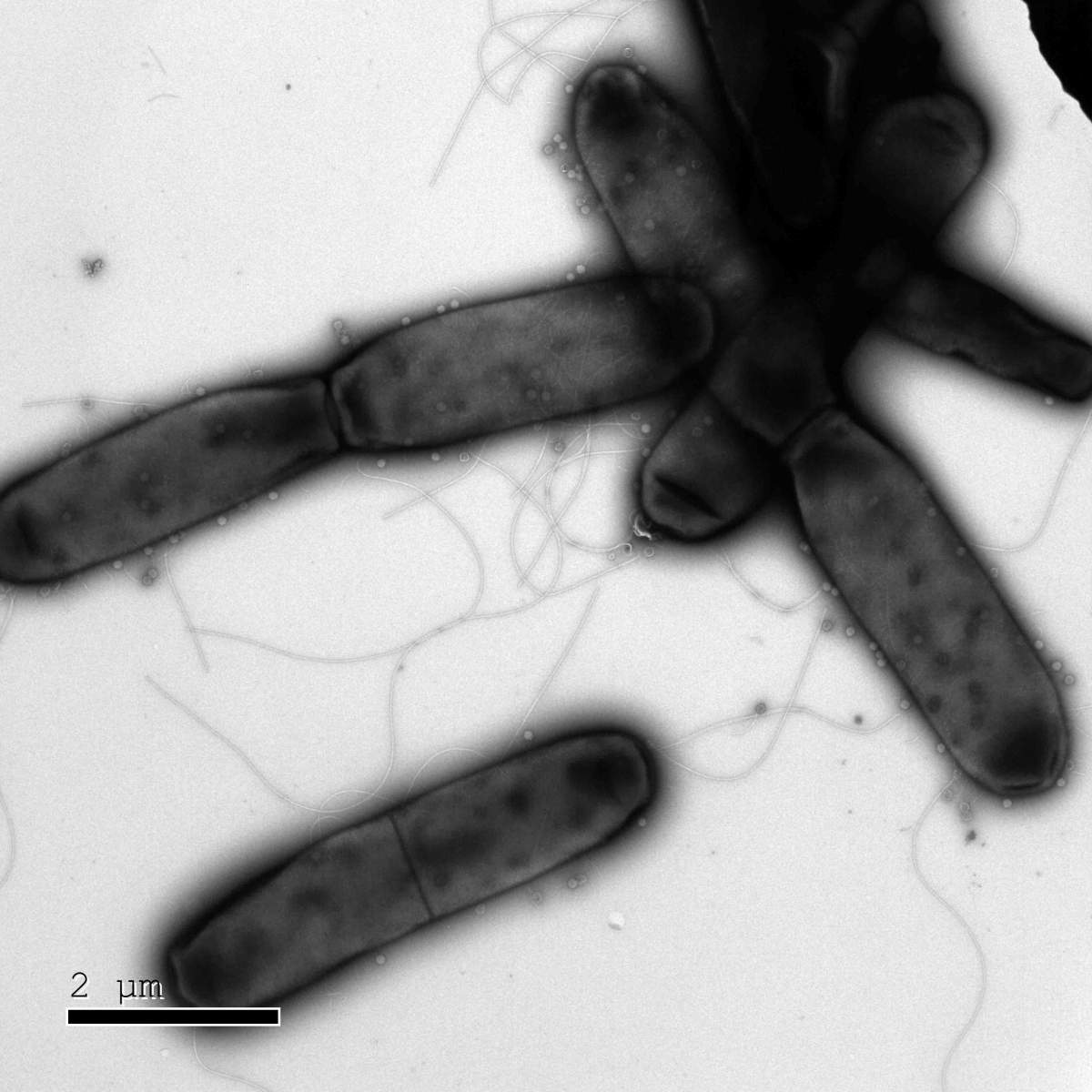

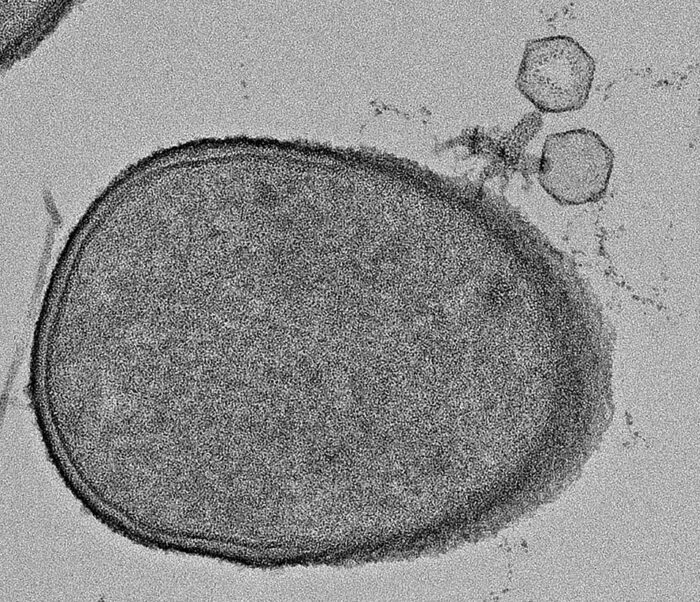

In particular, they are equipped to fight off phages – viruses that infect bacteria. These differ from the kind that infect humans in their choice of targets, but they all consist of genetic material – DNA or RNA – that hijacks parts of the host’s replication machinery to make copies of themselves and spread.

Sorek found that some of these bacterial immune responses suggest evolutionary links to our own immune systems, and the present study in his lab shows the strongest evidence yet: They discovered that viperin antiviral enzymes – whose function in the human immune system was understood only two years ago – play a role in the immune system of bacteria.

In humans, viperin belongs to the innate immune system, the oldest part of the immune system in terms of evolution. It is produced when a signalling substance called interferon alerts the immune system to the presence of pathogenic viruses. The viperin then releases a special molecule that is able to act against a broad range of viruses with one simple rule: The molecule ‘mimics’ nucleotides, bits of genetic material needed to replicate their genomes. But the viperin molecule is fake: It is missing a vital piece that enables the next nucleotide in the growing strand to attach. Once the faux-nucleotide is inserted into the replicating viral genome, replication comes to a halt and the virus dies.

This simplicity and broad action against many different viruses suggested viperins had been around for some time, but could they go back as far as our common ancestors with bacteria?

Led by former postdoctoral fellow Dr Aude Bernheim in Sorek’s lab, the group used techniques that had been developed in his lab to detect bacterial sequences encoding possible viperins. They then showed that these viperins did, indeed, protect bacteria against phage infection.

“Whereas the human viperin produces a single kind of antiviral molecule, we found that the bacterial ones generate a surprising variety of molecules, each of which can potentially serve as a new antiviral drug,” said Sorek.

Based on the genetic sequences, Sorek and his team were able to trace the evolutionary history of viperins:

“We found that this important component of our own antiviral immune system originated in the bacterial defense against viruses that infect them,” Sorek said.

If the bacterial viperins prove effective against human viruses, Sorek thinks it may pave the way for the discovery of further molecules generated by bacterial immune systems that could be adopted as antiviral drugs for human diseases.

“As we did decades ago with antibiotics – antibacterial substances that were first discovered in fungi and bacteria – we might learn how to identify and adopt the antiviral strategies of organisms that have been fighting infection for hundreds of millions of years.”

The current study was conducted in collaboration with researchers from Pantheon Biosciences, which has licensed the rights through Yeda Research and Development, the technology transfer arm of the Weizmann Institute of Science, to develop anti-viral drugs based on the findings. Further studies are underway to determine which of the bacterial viperins could be best adapted to fighting human viruses, including, of course, COVID-19. Also participating in this research were Adi Millman, Gal Ofir, Gilad Meitav, Carmel Avraham, Sarah Melamed and Dr Gil Amitai, all of Sorek’s group in the Weizmann Institute of Science’s Molecular Genetics Department.

Dr Aude Bernheim explains viperins

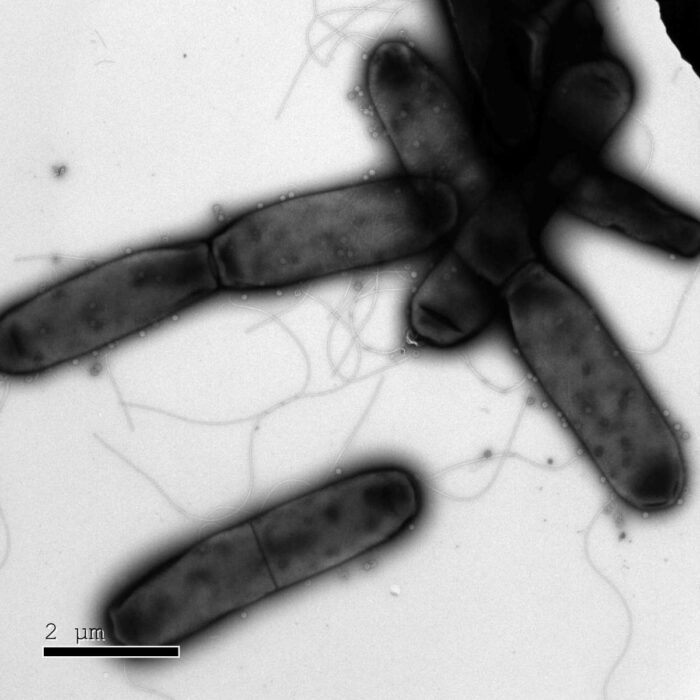

Viruses like the phages in the upper right specialize in infecting bacteria