September 26, 2011

The nose has long been viewed as a disorganized sensory organ, its odor receptors strewn about with very little rhyme or reason. A study in Nature Neuroscience, published online September 25, challenges that notion. It suggests that odor receptors are grouped by the pleasantness of the odors they detect.

The findings are creating “more than just a shake-up” among researchers who study olfaction, says Marion Frank from the University of Connecticut Health Center Graduate School. “It’s a tornado.”

Olfactory organization is especially obscure in humans. Rats’ odor receptors appear to be sorted by gene family, creating four distinct zones within the nostril. It is unknown whether those zones exist in the human nose, because to search for them would require tagging odor receptors with toxic chemicals. The human brain’s olfactory bulb is activated differently depending on where a smell hits the nostril, indicating that odor receptor organization is not uniform. However, most scientists agree that there is a large degree of randomness in receptor distribution.

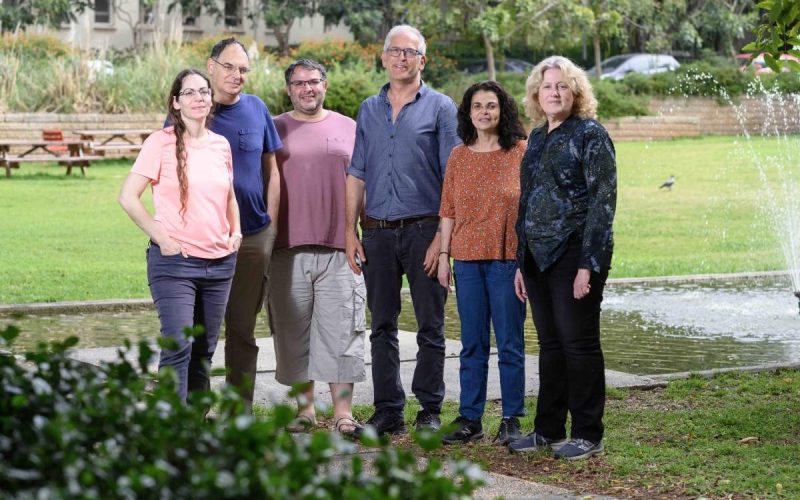

By inserting a Teflon-coated wire into the nostrils of nearly 60 volunteers, neurobiologist Noam Sobel from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, measured how small patches of the nasal lining respond to a variety of smells. Sobel’s team piped a variety of chemicals into the participants’ nostrils while the wire electrode recorded the reactions of neurons connected to the odor receptors. The participants evaluated the pleasantness of each smell: amyl acetate, which smells like bananas, received the highest overall rating for pleasantness. Garliclike diethyl sulfide received one of the lowest. Other chemicals, such as acetic acid (vinegar’s main component) elicited mixed reactions.

Sobel’s team administered one scent at a time to determine the responsive portions of the nasal lining. Some sites responded to the probe smell, whereas others did not, which reinforced the idea that odor receptors are not uniformly distributed. But what was most interesting was that if a pleasant odor was used to find the location, other pleasant smells had significantly strong neurological reactions at that site, too. Conversely, if an aversive smell was used to locate the recording site, subsequent noxious smells elicited strong reactions there as well. Furthermore, the smells that were rated most different in their degree of pleasantness also had the largest differences in neurological measurements.

These findings suggest that smell receptors are organized by the pleasantness of the aromas they detect—similarly to how retinas and ear cells are organized by spatial information and tone, respectively.

“I really didn’t want to believe it, but the data look strong,” says Don Wilson, who studies rat olfaction at New York University Langone Medical Center. In the past he and Sobel have disagreed over whether the molecules themselves provide information about the pleasantness of an odor, or whether it was the role of the brain to interpret scents. Wilson was surprised by the findings. “If you performed a similar experiment in vision, the equivalent results would be that we could use retinal activity to predict whether the eye is viewing a pleasant scene or an ugly one,” he says.

As Sobel points out, beauty is not all in the eye of the beholder—at least for the nose. “The popular notion that odorant pleasantness is subjective is wrong,” Sobel says. Just as a color or auditory tone is determined by the physical structure of its wavelength, scientists can predict an odor’s pleasantness based on its physical and chemical properties. The perception of an odor’s pleasantness or aversiveness is remarkably consistent across people and populations, Sobel says, and it’s one the most important evaluations an organism can make about a smell.

Richard Doty, director of the University of Pennsylvania‘s Smell and Taste Center, says the results should be taken with a grain of salt. “Pleasantness correlates with other psychological concepts, such as edibility and attraction or repulsion,” he says. He also said that future experiments should control for odor intensity, which can determine how pleasant or unpleasant an odor is. “For example, people who like the licorice odor anethole find it more pleasant as its concentration increases, whereas those who do not like licorice find it less pleasant as its concentration increases.”

If the odor receptors play a role in processing hedonic information, it is important to remember that the brain still plays a modulating role, Wilson says. “If I take isovaleric acid and tell you it’s going to smell like Parmesan cheese, you’ll smell Parmesan cheese, which will most likely be pleasant. But if I tell you it’s going to smell like vomit, you’re going to find it repugnant. It’s the same molecule, but your expectations influence how you perceive it.” Similarly to how the perception of a color is affected by the colors that surround it, the perception of a smell appears to be context-dependent.

The axis of pleasantness explains only part of the organization of olfactory receptors, Sobel cautions. Researchers are many years away from creating a topographic map of the nostril, but Sobel intends to be a part of that process. Currently, he and his team are rebuilding their electrode to have four probes, in order to take multiple measurements simultaneously. He’ll also approach it in a more systematic fashion, instead of just poking around to find an active region.

“Either the nose is not as clearly organized as other organs, or we’re not probing it properly enough,” he says.

http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=the-hedonic-nose